Whispers of Love and Light: A Private Journey Through Van Gogh’s Poets and Lovers

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh

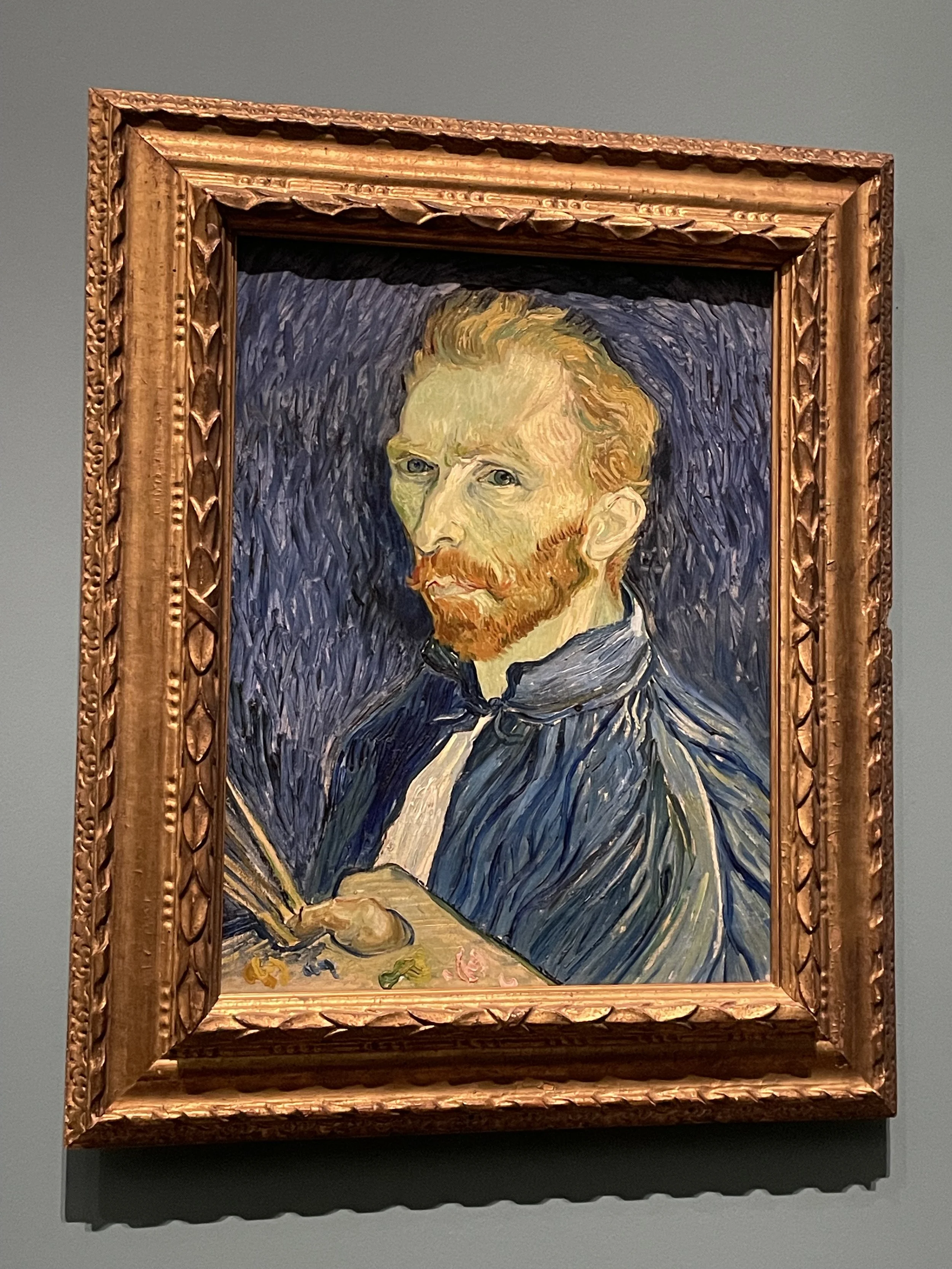

Vincent van Gogh, 1889

Whispers of Love and Light: A Private Journey Through Van Gogh’s Poets and Lovers

Vincent van Gogh is widely regarded as one of the most influential and emotionally expressive artists of the 19th century. Known for his vibrant use of color and his dynamic brushwork, van Gogh's work transcends mere representation of reality, offering a window into his turbulent emotional and psychological landscape.

A Private Tour of a Sold-Out Exhibition

Some moments in life feel like pure gifts; fleeting, rare, and profoundly moving. Four months ago, I had the incredible privilege of attending Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers at the National Gallery in London, a landmark exhibition celebrating the Gallery’s 200th anniversary. I was fortunate to attend the museum on a private tour, an experience so extraordinary that I still can’t quite believe it happened.

I was greeted at the museum’s entrance by one of the museum’s representatives. From there, I was escorted to meet one of the curators, who would walk me through the highlights of this remarkable collection. Simply walking through the exhibition was an honor but experiencing it through a private tour led by a curator transformed it into something unforgettable.

Every time I step into a museum, I feel incredibly fortunate—fortunate to stand before art that transcends time, to sense the presence of an artist’s hand in every brushstroke, and to lose myself in a world where color and emotion speak louder than words. But to witness an exhibition of this magnitude—one as monumental as the Vermeer retrospective at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands in 2023—was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

The National Gallery, London

Symbolic Portraits: People and Ideas

The exhibition offered an intimate exploration of van Gogh’s symbolic portraits, his time in the South of France, and the cultural influences that shaped his vision. Standing before his masterpieces, listening to the curator’s insights, I felt each brushstroke come alive—every hue, every layered emotion revealing itself in a new light. It was more than an exhibition; it was a journey into the very soul of van Gogh’s art.

The individuals depicted were often friends, mentors, or acquaintances who played pivotal roles in his life—sometimes through kindness, sometimes through conflict. His relationships with poets and lovers deeply influenced his creative vision.

During his time in southern France, van Gogh frequently depicted strolling couples, an archetype that became a recurring motif in his work. These figures symbolized love, aspiration, and reflection. The women, often wearing the distinctive fichu (a shawl worn by women from Arles), connected back to van Gogh’s observations of local beauty and culture.

Inspired by theVenus of Arles in the Louvre, he arrived in the region with strong cultural expectations about the people and landscapes he would encounter.

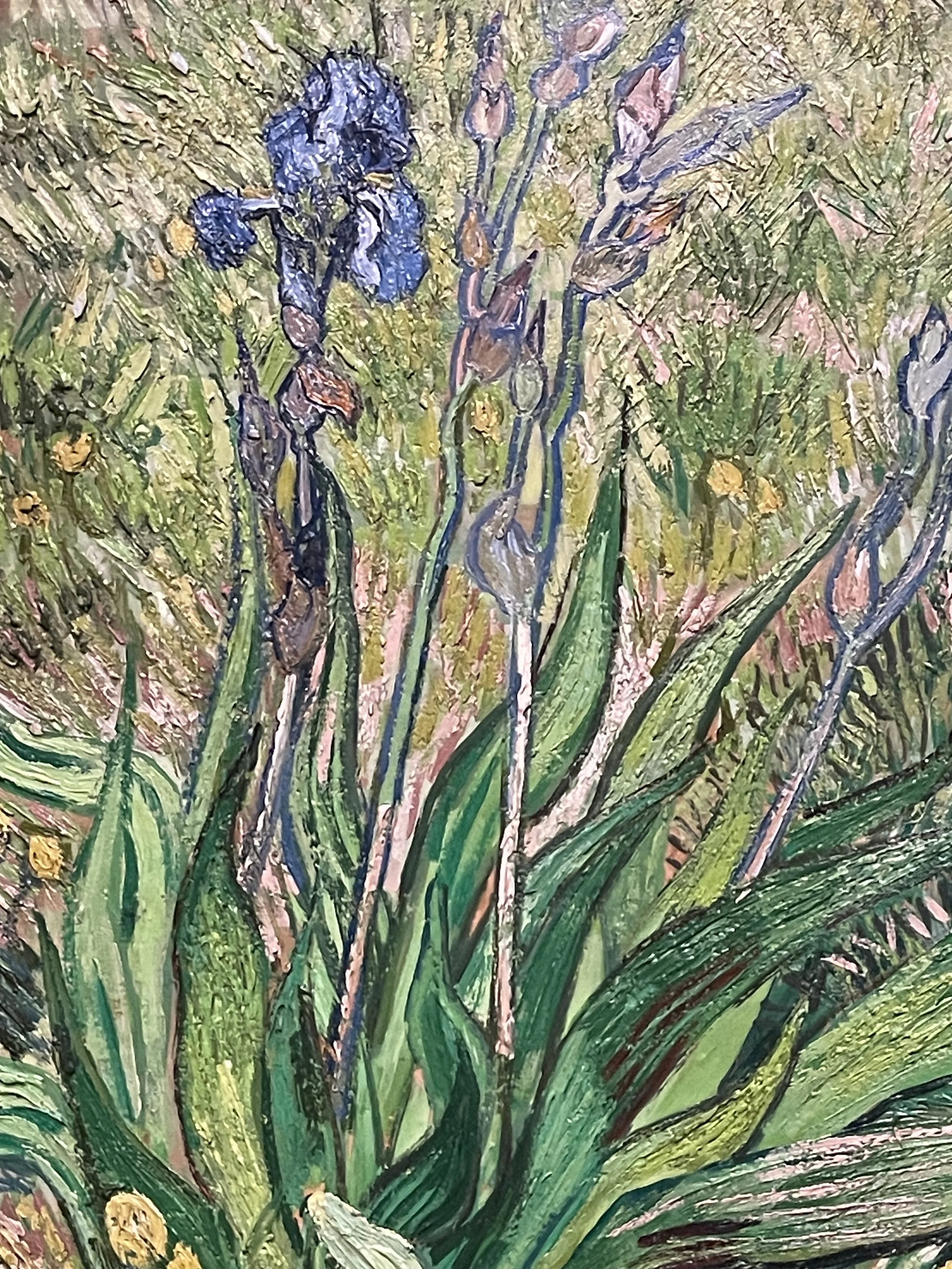

The Garden of Inspiration

A significant portion of the exhibition was dedicated to van Gogh’s studio and the nearby public park, where he spent countless hours in contemplation. These locations were central to his creative process. The park, directly opposite his studio, provided both inspiration and a place for personal reflection. The displayed works showed various times of the day, illustrating how shifting light and color transformed the garden through van Gogh’s vivid brushstrokes.

Due to the intense heat, van Gogh likely took morning strolls in the park and painted during the cooler evenings, sometimes even by candlelight. One particularly striking painting features a figure in the park wearing a straw hat and a work jacket while holding a newspaper. This figure is believed to represent van Gogh himself. The inclusion of a self-portrait here suggests van Gogh's ongoing introspection and self-exploration through his art.

The Role of Letters and Connection to Other Artists

Van Gogh’s correspondence with his brother Theo and other artists plays a crucial role in understanding his work. His letters offer insights into his thoughts on color, composition, and technique. A recurring theme in these letters is van Gogh’s engagement with the artistic community. Subscribed to several art journals, he regularly received critiques and feedback—both positive and harsh—on his work. This exchange of ideas was vital to his growth as an artist, even though he rarely sold his paintings during his lifetime.

Theo played a pivotal role in supporting Vincent’s career, often sending his works to exhibitions and critics. Even when they did not find commercial success, they were seen and appreciated by those in the art world. Vincent’s meticulous attention to detail extended beyond painting; he would instruct his brother to frame his works in specific materials, such as walnut or beech, ensuring they were presented properly.

Van Gogh’s Bold Use of Color and Symbolism

A standout feature of the exhibition was its focus on van Gogh’s groundbreaking use of color. His famous declaration, “I’m going to use color arbitrarily to express myself,” captured his departure from realism and embraced a more emotive, symbolic approach to color. This transformation was evident across his portraits, landscapes, and self-portraits alike.

Standing before Starry Night Over the Rhone, it’s clear that for van Gogh, color wasn’t just about representation—it was a language of emotion. He played with complementary contrasts, like deep blues paired with golden yellows, to evoke movement and energy. Yellow and violet spoke of joy and sorrow, blue and orange of night and firelight. Each brushstroke became a vessel for his inner world.

Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888

A Self-Portrait Born from Crisis

One particularly striking painting in the exhibition is a self-portrait from Washington, created after the infamous crisis of 1888 when van Gogh cut off part of his own ear. This self-portrait shows him with his head tilted just so, to avoid revealing the area of his ear that had been injured. His complexion appears sallow, which was likely an unintended result of the red geranium pigment he used in his paintings. This pigment, known for being fugitive (meaning it fades over time), could have distorted the color of his skin, giving it a greenish hue. Nonetheless, the emotional weight of this self-portrait remains unmistakable, capturing the artist in a moment of physical and emotional turmoil.

Painting Beyond Representation

When van Gogh spoke of using color arbitrarily, he wasn’t simply talking about throwing paint on a canvas for shock value. Rather, he was declaring his intent to break free from the constraints of realism and push toward an expressive, almost symbolic, use of color. As the curator pointed out, van Gogh knew how to paint realistically—he had the skills to depict figures and scenes in their true-to-life colors. But in the paintings shown in the Poets and Lovers exhibition, he shifts away from that, opting instead to paint objects and scenes based on his emotional responses to them.

If van Gogh saw something as blue, for instance, he didn’t hesitate to paint it his own unique shade of blue and often surrounded it with an orange line. This wasn’t about the literal color of the object; it was about what that color represented for him emotionally. His use of complementary colors was deliberate, meant to heighten the emotional impact of the piece rather than replicate reality. He rarely used black in his paintings, instead choosing to saturate his work with brighter hues that spoke to the emotions and energy he wanted to convey.

The Yellow House and the Dream of Collective Creativity

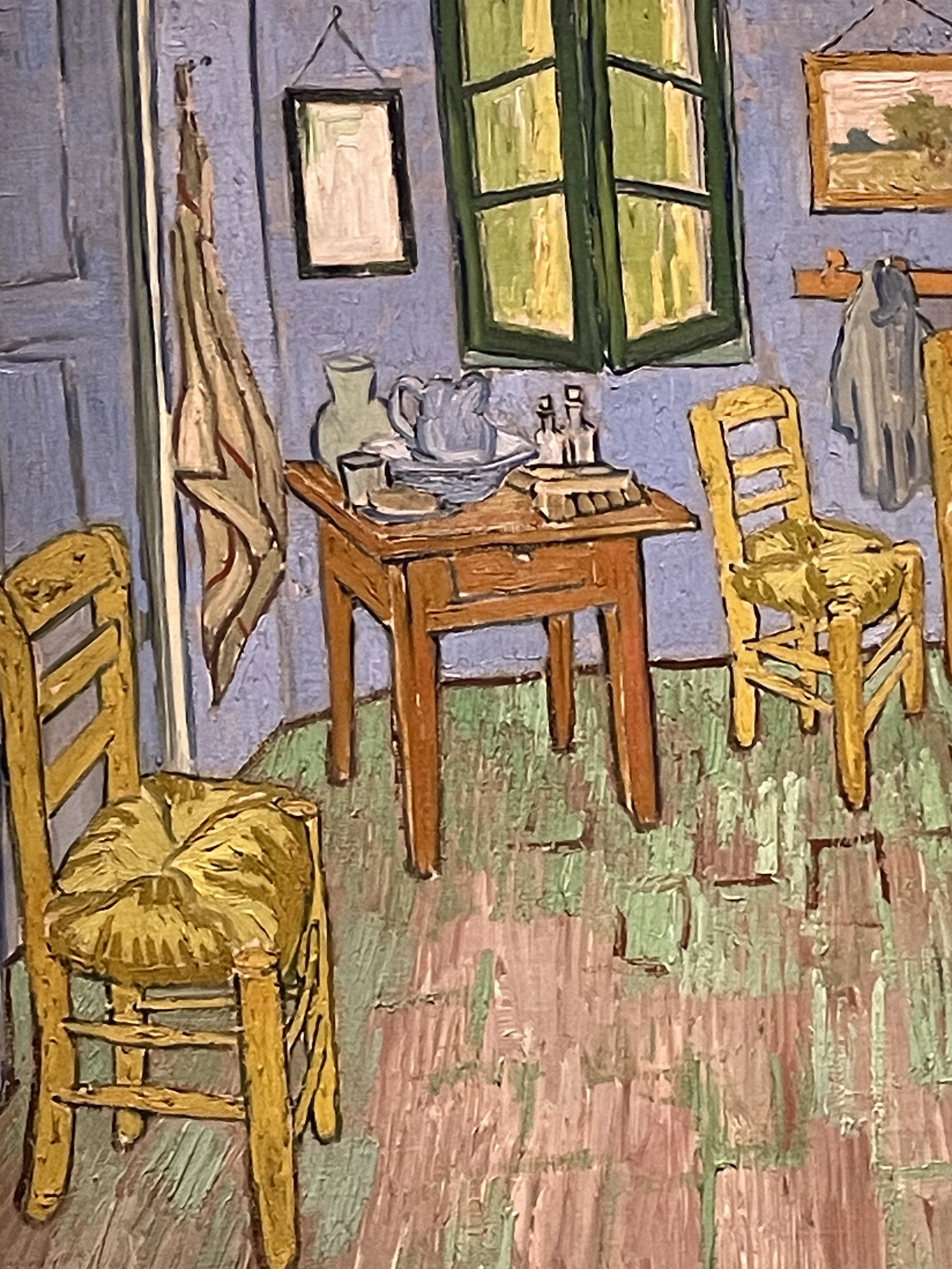

Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles, painted in October 1888, was created as he anticipated the arrival of Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh had big plans for his time in the South of France, hoping the region would provide new inspiration for artists feeling stifled by the Parisian art scene. He even decorated his house, hanging portraits of friends and poets, and purchased twelve chairs in preparation for a shared artistic environment. Though Gauguin was the only one who agreed to join him, van Gogh's vision of a collaborative space reflected his deep desire for connection and creative companionship.

This version of Bedroom in Arles is the third in a series and includes personal details that reveal van Gogh’s relationships. In this iteration, van Gogh places himself where his friend Millet, a lover in an earlier version, once stood. On the opposite side of the room is the poet Eugen Bosch. These changes suggest that van Gogh was integrating himself into the narrative of his own life, reflecting not only his connections with these individuals but also his feelings of isolation and longing for companionship.

Interestingly, a smaller version of the painting was sent to his mother, where van Gogh appears healthier, and the mysterious woman is absent. In this version, his self-image is clearer, and it offers insight into how we often modify our personal stories when sharing them with others, even those closest to us.

Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles is a pivotal work in the exhibition, showcasing his pursuit of simplicity and tranquility through color and composition. In a letter, van Gogh describes the bedroom’s furniture and calming hues, carefully selected to create a sense of peace. The walls are painted in soft lilac, the floor in faded red, while the furniture—bed, chairs, and pillows—features bold contrasting colors, creating a harmonious yet dynamic visual experience. He hoped these contrasting tones would evoke a sense of total repose, highlighting the balance he sought to achieve in his work.

Notice the details of the paintings hanging on the walls of the three different version. On the first version (part of the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, are both The Poet and The Lover side by side, as they were hanged together once again at the beginning of the exhibition.

The emotional connection between van Gogh and the paintings he created in this room is undeniable. He describes the peace he found in the space, despite the turmoil in his life. This bond between the artist’s emotional state and his work is a powerful aspect of van Gogh’s letters, which many find moving. To me, reading these letters stirs deep emotions, as they reveal van Gogh’s profound love for humanity and the pain of being misunderstood. His vulnerability and yearning for connection shine through in his writing, making his art all the more poignant.

The Yellow House (The Street), 1888

A Reunion of Sunflowers

And then, there were the Sunflowers.

I have stood before the Sunflowers at the Philadelphia Museum of Art more times than I can count. I know it’s every swirl, every shade of ochre and gold. My first trip to London was to see the Sunflowers from the National Gallery, and I have travel to Boston specifically to see La Barceuse at the Museum of Fine Arts before. To see them all three of them here, alongside their siblings, as Vincent always intended them to be displayed, was nothing short of breathtaking.

The Sunflowers are more than still-life paintings. They are portraits of light, of devotion, of life itself. Seeing the Sunflowers reunited after so many years apart was a profound experience, allowing a rare glimpse into van Gogh’s emotional connection with his subjects.

Interestingly, the Sunflowers from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (with a blue background) were displayed in a much simpler frame than their original. This choice was made to match the 17th-century frame of the Sunflowers from the National Gallery (with a yellow background). The curators at the Philadelphia Museum of Art made this unusual decision to create a more visually cohesive and appealing triptych.

This was the part of the exhibition I was most looking forward, a once in a lifetime experience.

Triptych presentation of the London and Philadelphia Sunflowers surrounding La Berceuse

Sunflowers, 1889. Philadelphia Museum of Art, in its original ornate gilded frame.

A Life Shaped by Legacy

Van Gogh was acutely aware of the mark he wanted to leave on the world. His concern for legacy extended beyond his paintings to the objects and symbols that surrounded him. Inspired by Egyptian funerary art, he saw personal belongings not just as decorations but as elements of a narrative that could endure beyond life itself. This fascination influenced his arrangements in paintings, where objects are often positioned in profile or relief, mirroring ancient funerary sculptures. His art was his way of asserting permanence in a world that felt fleeting.

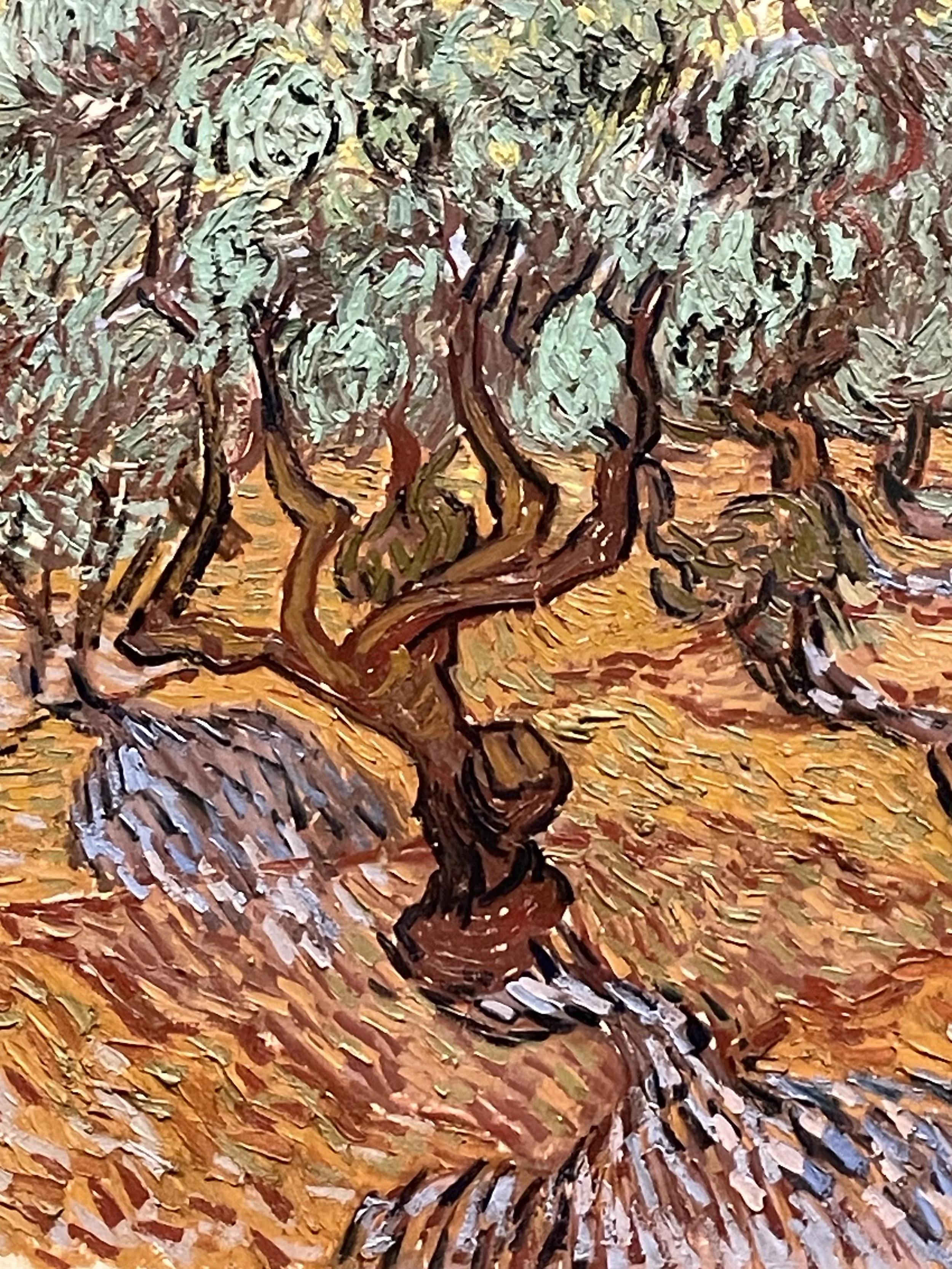

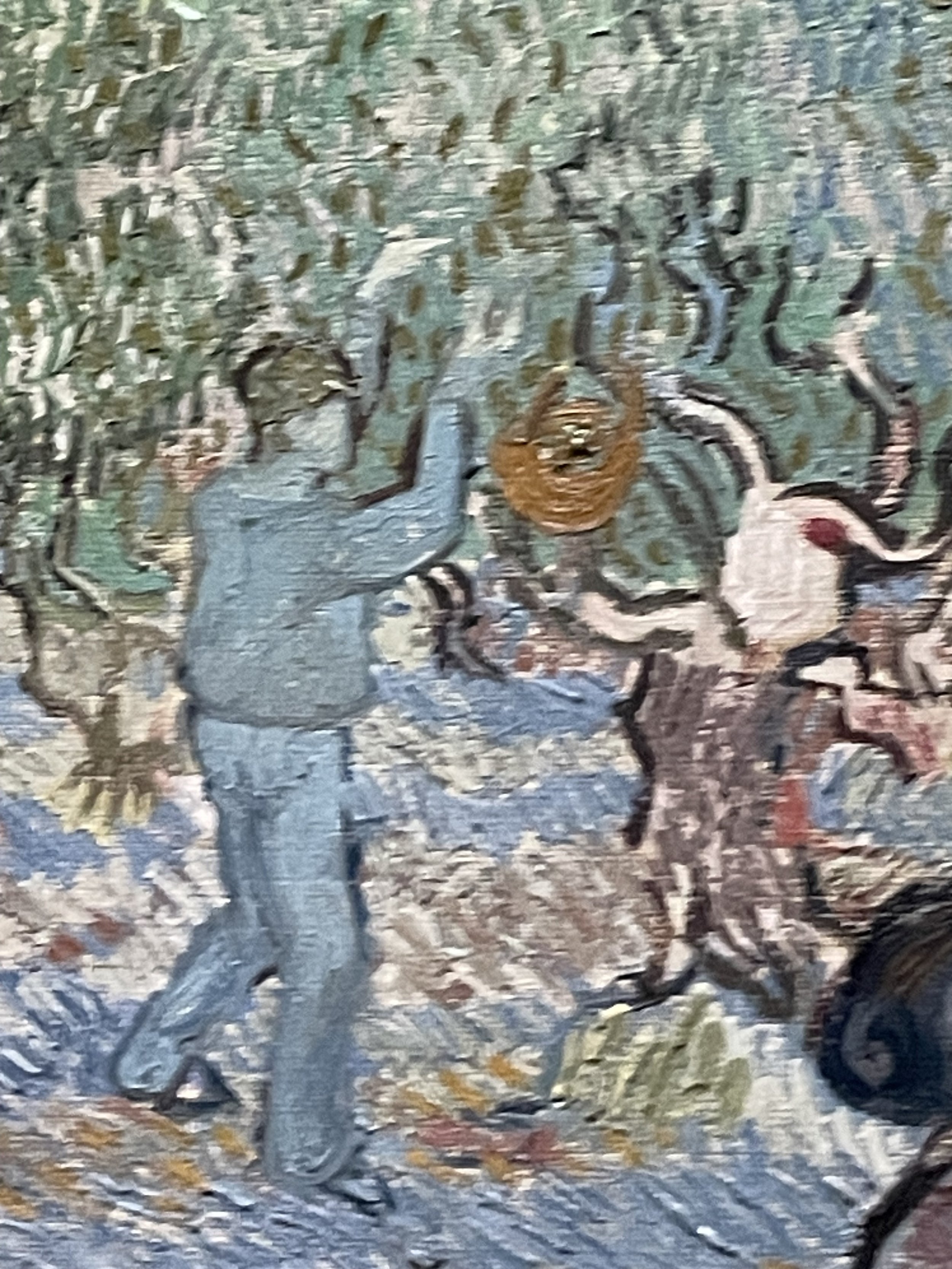

Recovery Through Art: Saint-Rémy and Beyond

Van Gogh’s time at the Saint Paul de Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy marked a crucial period in his life. There, he found solace in painting, capturing olive groves, cypress trees, and the Alpilles Mountains. His art became a form of therapy, a way to process inner turmoil while engaging with the world outside. Supported by progressive figures like Dr. Théophile Peyron and Pastor Frédéric Sévégny, Van Gogh was able to continue creating, proving that art was not just his passion but his salvation.

The Emotional Weight of His Letters

More than just historical artifacts, van Gogh’s letters are emotional documents that allow us to witness his joys, frustrations, and philosophical musings. They reveal an artist deeply attuned to the tension between tradition and modernity. His love for rural France, particularly Montmajour, reflected his longing for a simpler existence even as he saw industrialization encroaching upon the landscapes he cherished. Through his words, we understand not just the artist, but the human being who felt deeply, loved intensely, and struggled profoundly.

The Challenge of Modernity

In one of his famous works, van Gogh painted the Elysian Fields, a Roman burial ground in Arles, with a unique perspective that contrasts the peacefulness of the site with the encroaching modernity around it. The factories in the background are exaggerated in size, drawing attention to how industrialization and progress were shrinking spaces of tranquility, something van Gogh felt keenly. The fall of autumn leaves and the vibrant colors in his painting were, for him, more than just an aesthetic choice; they were his way of expressing the tension between nature and human expansion, a recurring theme in his work.

The way van Gogh used color and composition to convey his thoughts on modernity is remarkable. The green of the leaves and the abstraction in the lower part of the canvas are both symbolic and visually arresting, revealing his deep engagement with both the natural world and the changes happening around him.

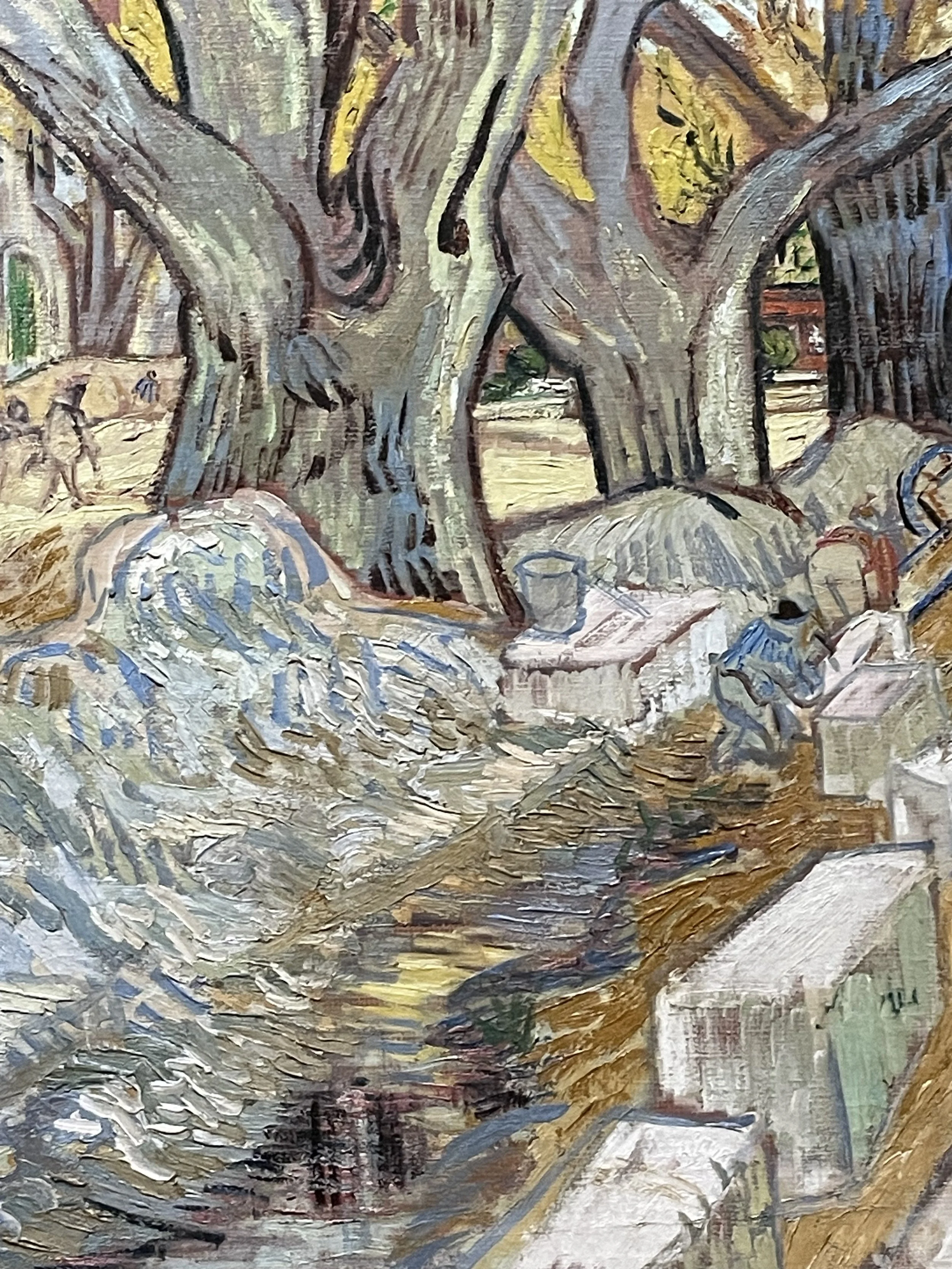

A Picture of Neighborliness

One of the paintings discussed, The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy), captures a moment of ordinary life but also speaks to the larger changes taking place in van Gogh's world. The installation of gaslight and the digging up of streets represent the encroaching industrialization, which often conflicted with van Gogh’s idealized view of rural life. His use of bold colors and patterns, like the carmine red of a tablecloth, reflects his attention to detail and his sense of realism, showing how even mundane elements can carry deep meaning. The use of space and the balance between the vibrant and empty parts of the canvas gives a feeling of rest, a rare moment of calm amidst the chaotic changes.

Portraits and Personal Connections

The portraits of Madame Genoux and other figures reflect van Gogh’s ongoing connection with individuals who, in various ways, mirrored his own experiences of pain and healing. His depiction of Madame Genoux, especially her intellectual engagement with literature like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, speaks to van Gogh’s deep empathy and his desire to understand the hardships of others, particularly women. There’s something profoundly moving in the way van Gogh not only paints her but also connects with her on an intellectual level, bonding over shared readings and mutual suffering.

The relationship between van Gogh and his subjects—whether friends, neighbors, or intellectual equals like Madame Genoux—is essential to understanding his work. He didn’t merely paint portraits or landscapes; he engaged with his subjects on a deeply personal level, seeking meaning and beauty in their lives and struggles. Through his art, van Gogh processed and transcended his own pain, using it as a means to communicate with others and to create a legacy that would endure long after his death.

Feminism and Empathy

The notion of van Gogh as a "proto feminist" is especially striking. His letter to his sister, in which he expresses an interest in understanding women's work better, shows a tender and thoughtful side of him, one that sought to understand and appreciate the struggles of those around him. This intellectual curiosity, paired with his emotional sensitivity, adds another layer to his character and his art, making him more relatable and empathetic than he might often be portrayed.

The Spiritual Power of Montmajour

Beyond his exploration of color and form, van Gogh’s letters provide insight into his philosophical musings on life, art, and society. A recurring theme in his correspondence is the tension between tradition and the encroachment of modernity. In these letters, he expresses a deep affection for the simple beauty he found in rural France, particularly in Montmajour, an ancient Benedictine Abbey nestled in the rocky hills outside Arles. Yet, even there, van Gogh observed the creeping effects of industrialization, which he felt threatened the purity and tranquility of the landscapes he cherished.

The Montmajour series, a collection of drawings made by van Gogh between 1888 and 1889, offers another perspective on his deep engagement with nature. The rugged, untamed beauty of Montmajour, with its stony hills and sparse vegetation, provided an ideal setting for van Gogh’s expressive techniques. These drawings, renowned for their intricate cross-hatching and bold lines, served as preparatory studies for his later paintings, but they also stand as powerful works of art in their own right. They capture not only the physical landscape but also the spiritual and emotional resonance van Gogh found in the terrain.

One of the most iconic works in the series, View of La Crau from Montmajour, exemplifies van Gogh’s ability to distill the essence of a scene into its most expressive form. The dynamic lines and contrasts in the drawing foreshadow his later paintings of wheat fields and cypress trees, where he continued to explore the emotional weight of nature’s forms. Montmajour itself—the Abbey, the surrounding terrain, and the skies—captivated van Gogh with its sense of history. As he wrote to Theo, the ruins and natural world seemed to speak of timelessness, inspiring both his art and his personal reflections.

Interestingly, Sunset at Montmajour, a painting believed to have been lost for decades, was rediscovered in 2013. Initially misattributed, it was eventually confirmed as a genuine van Gogh masterpiece. This painting beautifully captures the rugged beauty of Montmajour, mirroring the same terrain van Gogh had explored in his sketches. Its rediscovery is not only a thrilling moment in the history of van Gogh’s work, but it also reinforces the profound connection he felt to the region, cementing Montmajour’s significance in his artistic development.

View of La Crau from Montmajour, 1888 (For conservation reasons, this drawing was on display only for the first month of the exhibition

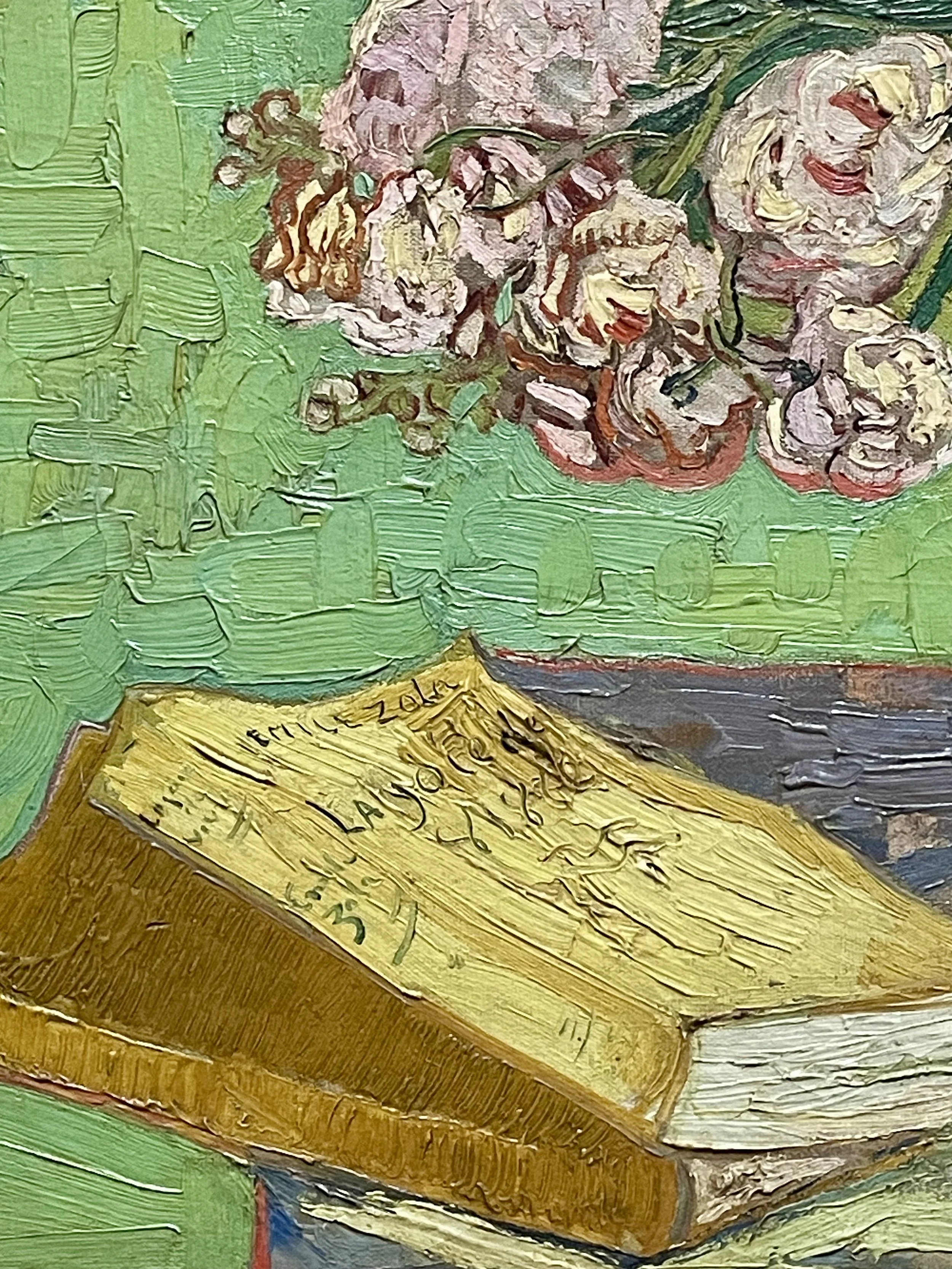

Van Gogh and Émile Zola's The Sin of Abbé Mouret

Van Gogh was an avid reader and had a deep admiration for the French writer Émile Zola, whose naturalist novels often portrayed the struggles of the working class and the raw realities of life. One book that particularly captured his attention was La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret (The Sin of Abbé Mouret), published in 1875.

The novel tells the story of Abbé Mouret, a young priest who, after suffering a nervous breakdown, recovers in a lush, Eden-like Garden. There, he falls in love with a young woman named Albine, which leads to a profound internal conflict between his religious vows and his natural human desires.

Van Gogh read The Sin of Abbé Mouret around 1880–1881, during a time when he was transitioning from a failed career as a preacher to becoming an artist. He deeply resonated with the novel's themes of religious struggle and the overwhelming force of nature. At the time, van Gogh had just abandoned his missionary work in the Borinage, Belgium, where he had lived in extreme poverty and faced a personal crisis similar to that of Abbé Mouret. The novel’s contrast between religious devotion and earthly beauty likely influenced van Gogh’s own evolving views on spirituality and nature.

Zola's vivid descriptions of landscapes and nature may have also impacted van Gogh’s artistic vision. The novel’s garden, almost a character in itself, is filled with wild, untamed beauty, much like the natural settings Van Gogh would later paint with his expressive, swirling brushstrokes.

In examining van Gogh’s art, it becomes clear that his work was not just a representation of the external world but an emotional experience—a journey of self-exploration and grappling with the complexities of the human condition. His paintings, infused with both color and emotion, continue to captivate and resonate with audiences worldwide. Van Gogh’s legacy is one of raw emotional intensity, a reminder of the beauty that exists in the fleeting, in the everyday, and in the search for meaning that defines the human experience.

Legacy of the Artist

These reflections on van Gogh’s life and work are not only about the art itself but also about the enduring humanity that runs through it. Despite his mental health challenges, his work, letters, and relationships all speak to his desire to connect with the world on a deeper level. His legacy is one of raw honesty, intellectual curiosity, and a profound sensitivity to the human condition.

A Once-in-a-Lifetime Experience

The Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers exhibition, which closed at the National Gallery in London on January 19th, offered a rare opportunity to delve deeply into the artist’s life and work.

Spanning over fifty works, the exhibition charted van Gogh’s artistic evolution, from his early self-portraits to his later explorations of color, light, and emotional depth. It also spotlighted van Gogh’s symbolic portraits, which went beyond mere likenesses of their subjects to infuse them with profound layers of meaning. Particularly during his time in the South of France, these portraits reflected van Gogh’s deep engagement with the personal and spiritual aspects of his relationships.

As seen in works like Starry Night Over the Rhone, van Gogh’s move to Arles marked a pivotal moment in his use of color. The dazzling light of the South, with its golden wheat fields and vibrant skies, inspired a dramatic shift in his palette. Here, van Gogh employed complementary color contrasts, not merely for visual appeal, but as a means of conveying profound emotion. The swirling skies and shimmering reflections in Starry Night evoke a sense of movement and energy, drawing the viewer into his emotional landscape. His use of impasto—thick, textured strokes of paint—heightened this emotional intensity, transforming each canvas into a dynamic, living entity.

Yet, for all his emotional intensity and bold experimentation, van Gogh’s art remains profoundly human. His exploration of love, companionship, and loneliness pervaded his work, resonating in pieces like Sunflowers. Often regarded as a symbol of Vanitas, this series reflects the fleeting nature of life, and the beauty found in its transience. The Sunflowers paintings, displayed together for the first time in decades during the exhibition, reveal the artist’s deep emotional connection to the subject, his brushstrokes alive with energy and movement.

For those fortunate enough to have experienced the Poets and Lovers exhibition, the journey through van Gogh’s world was not just visual, but deeply emotional—an invitation to connect with the artist’s inner life and, in turn, with our own. Through both his paintings and letters, van Gogh’s art speaks to the heart, offering not only a glimpse into his world, but also into the timeless, universal quest for beauty, meaning, and connection.

As I left the exhibition, I carried with me not just the memory of van Gogh’s paintings but the sense of urgency and passion that fueled his work. He painted because he had to, viewing the world through the lens of color and movement, believing that art held the power to console, much like music.

Leaving the exhibition, I was reminded that van Gogh’s art is not merely a window into his world but a timeless invitation to reflect on the depth of the human experience.

I am immensely grateful to those who made this experience something I will always treasure.

I have created a PDF file with all the artworks in the exhibition exclusively for you. To download the full list of artworks featured in the Poets and Lovers exhibition in order of which they were displayed (all 61 of them!), click the link below. Included is the museum or entity where they belong, with a corresponding link. Enjoy!

My Own Sunflowers

Ever since I can remember, sunflowers have been my favorite flowers.

A few years ago, after studying in depth van Gogh’s technique and the colors he used, I did my own version of Sunflowers, using his same palette and high impasto as he did in his paintings. It was such an emotional and learning experience.

I have enjoyed having the sunflowers in my home these past four years, I am now ready to let them go to a new home.

To purchase my Sunflowers, click on the image below.